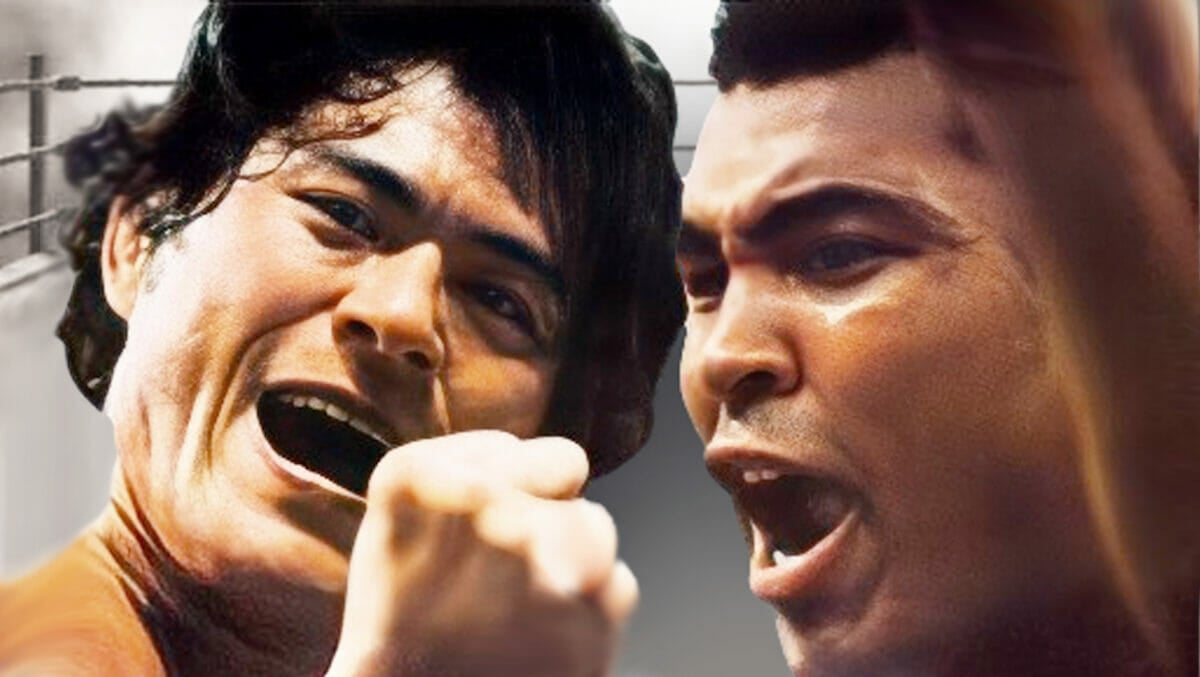

On June 26th, 1976, two decades before MMA came onto the scene, a bizarre encounter between Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki became the talk of the sports world.

Quick Tip for Facebook Readers

Many of our readers connect with our content through our Facebook page. However, Meta's built-in browser (which opens by default on mobile) occasionally freezes mid-article- a known issue unrelated to our site. To enjoy uninterrupted reading: Tap the three dots in the top right corner → Select 'Open in external browser.' This will resolve the glitch. Thanks for your support. We want your wrestling stories to stay as smooth as a top-rope hurricanrana!

“His leg is badly bruised. It is red. It is raw. And I don’t know how long those beautiful legs of Muhammad Ali are going to be able to take those kicks.”

– Color commentator Jerry Lisker

Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki – The Fight that Inspired MMA

With a 53-2 record, Muhammad Ali is considered one of the greatest boxers of all time.

He entered the bout against Antonio Inoki as the undisputed WBC/WBA World Heavyweight Champion. Set to take home $6.1 million for the fight against a Japanese wrestling legend, Ali tried to put the media at ease. Minutes before the match, the press was still uncertain if the bout would be legit.

“I wouldn’t take the sport of boxing and disgrace it,” proclaimed Ali. “I wouldn’t pull a fraud on the public. This is real. Everything is going to be real.”

From the start, Antonio Inoki treated the bout as a genuine fight.

“Inoki was a scary guy,” said publicist Bobby Goodman who worked with Ali in Tokyo on behalf of Top Rank. “He was always calm and spoke in a casual way, about breaking Ali’s arm, or pulling out a bone, or a muscle.”

Many questioned the boxer’s sanity over wanting to fight a wrestler. After 15 three-minute rounds, Antonio Inoki landed over a hundred kicks, mostly on Ali’s left leg. It almost jeopardized his career.

Let’s take a closer look at the match billed as “The War of the Worlds.” It is often considered the first big MMA fight (or flop?) in history.

“Boxing is old news. We’re in a new field now. We’re going to Japan to take on this Antonio Inoki, the World’s Heavyweight Karate Champion. I predict this will outsell all of my fights, and I’m the biggest draw in the world. Everybody should watch this fight.”

– Muhammad Ali on The Tonight Show, June 14th, 1976.

Boxer vs. Wrestler: The Precursor To MMA

The idea of a wrestler and a boxer engaging in a no holds barred encounter is a timeworn debate that goes back to the 1920s when a confrontation between the ever-popular champion pugilist Jack Dempsey and matman extraordinaire “Strangler” Lewis never materialized and remained only as an unfulfilled fantasy matchup.

But documented mixed style matches go as far back as antiquity with the Romans and the Greeks, where an opponent losing a limb or even dying wasn’t unusual.

Fighting arts like karate, kickboxing, taekwondo, judo, boxing, kung fu, and wrestling claimed superiority. But now we know that someone who can combine all of these styles flawlessly makes for the most capable fighter.

In April 1975, Muhammad Ali met Ichiro Hatta, an Olympian, and president of the Japanese Amateur Wrestling Association, at a reception in the United States.

As explained in the book Ali vs. Inoki: The Forgotten Fight That Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment by Josh Gross, the story goes that Ali nudged Hatta with a dare. “Isn’t there an Oriental fighter who will challenge me? I’ll give him one million dollars if he wins.”

Respected for, among many things, introducing Western-style wrestling to Japan in 1931, Hatta devoted himself to grappling.

Unbeknownst to Ali, Hatta was the best person to relay his message to a Japanese press who predictably played up the remark. Antonio Inoki answered the challenge, and the wheels were in motion for one of the most bizarre bouts ever witnessed still to this day.

Why Muhammad Ali?

Decades away from MMA becoming an organized, professional sport and worldwide phenomenon, boxing was considered THE combat sport in the seventies. Muhammad Ali was the undisputed champion standing atop that mountain.

So why would he agree to fight a wrestler? There was no way this would be anything but an exhibition, and nobody with any sense would allow Muhammad Ali to get injured in some phony wrestling show, right?

So why agree to a match in a sport that was foreign to him that could be to his physical detriment three months before his rubber match (third and deciding bout) against Ken Norton? Well, $6.1 million will motivate most people to do almost anything!

Some speculate that Ali’s constant search for wealth drove him to diversify. He was going through a costly divorce, supported many mistresses, his parents, and his traveling entourage was sometimes close to 50 people.

“People always wondered: ‘How would a boxer do with a wrestler?’ I’ve always wanted to fight a rassler, and now I’m going to get a chance to do it,” explained Muhammad Ali when promoting the upcoming match on June 14th, 1976’s episode of The Tonight Show.

Before this, he also had three boxing bouts against Jean-Pierre Coopman, Jimmy Young, and Richard Dunn. Although these opponents weren’t top caliber, and some boxing aficionados would even label them as “glorified sparring partners,” Ali was pushing his body to the limit a few months before facing Inoki in a match the specialized fighter wasn’t familiar with.

Shortly after the fight’s official announcement, Ali got his first taste of in-ring action after Gorilla Monsoon gave him an airplane spin and slammed him on the mat. Ali also had two worked matches versus wrestlers, Kenny Jay and Buddy Wolfe on ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

Antonio Inoki: A Man on a Mission

Antonio Inoki, a student of Rikidozan, had a mission where he wanted to prove that pro wrestlers could fight the best in the world and against any other fighting style.

In Japan, Inoki made a name for himself, facing opponents of various disciplines in worked shoot-style matches to elevate wrestling’s portrayal as a legitimate combat sport.

From 1975 to 1989, Inoki “fought” in twenty mixed martial arts contests, most being “worked” and a few others legitimate.

The Wigan-trained Karl Gotch, who would be in Inoki’s corner as an advisor in the bout versus Ali, became the backbone and head trainer of New Japan Pro Wrestling. Until then, Antonio Inoki, one of the most famous athletes in Japan, remained largely anonymous outside of his country. But in a match against Muhammad Ali, he was assured global exposure.

Inoki prepared for Ali as one did for a real fight and was ready to slay the “Louisville Lip,” who questioned his skills and legitimacy.

With hundreds of amazing Pro Wrestling Stories to dive into, where do you start? Get the inside scoop – join our exclusive community of wrestling fans! Receive 10 hand-picked stories curated just for YOU, exclusive weekly content, and an instant welcome gift when you sign up today!

Taking Trash Talk To An Art Form

Muhammad Ali officially announced his participation in the Antonio Inoki match at a New York City news conference in late March 1976 at the Plaza Hotel. The two competitors weren’t at a loss for words and did their finest to promote the match, but Ali was especially animated.

Inoki took the stoic approach when under the verbal assaults of Ali but still held his own.

“When the wind blows, I shall bend but not break,” Inoki said through a translator, answering Ali’s incessant blathering.

Ali continued and said while holding up his fist that he couldn’t miss Inoki’s protruding jaw. This was when he began referring to him as “The Pelican.”

Inoki smiled and quipped, “When your fist hits my chin, I hope you do not hurt your fist.” He also said he hoped Ali didn’t duck out at the last minute.

“If I ain’t afraid of walkin’ down a back alley in Harlem, I ain’t afraid of you,” answered Ali, refusing to be bested in his own game.

“I think Ali thought it would be more of a show,” said publicist Bobby Goodman. “But the first time we got together with them about the do’s and dont’s and rules of the fight, it became very obvious to me that Inoki’s people were serious.”

And without a rehearsal of how the match was going to go, Ali and his people were determined to protect the champion somehow and make sure he wasn’t embarrassed or, even worse: injured.

In the same press conference, the seven-foot, 500 lbs André The Giant shared the stage with Ali.

Ali craned his neck and asked the massive André, “You think you can beat me up?”

And to this, André half-jokingly answered in his booming voice, “I could beat you up and throw you out of the building.”

Muhammad Ali – Learning From Gorgeous George

Muhammad Ali was no stranger to wrestling and admired its histrionics.

The “Human Orchid” Gorgeous George — who’d tell everyone he’d win his matches because he was the prettier wrestler — was instrumental in helping Ali become the brash, trash talker everyone loved or hated but wanted to see.

In June 1961, in Las Vegas, after observing how everyone booed and despised Gorgeous George, Ali absorbed everything he witnessed and decided he’d never be shy again about expressing himself. He included wrestling-style theatrics in press conferences that made his bouts feel like something unmissable.

After wrestling a no-contest bout against Freddie Blassie, Gorgeous Geroge offered some advice to Ali in the locker room: “You got your good looks, a great body, and a lot of people will pay to see somebody shut your big mouth. So keep on bragging, keep on sassing, and always be outrageous.”

Celebrating America’s Bicentennial

In the summer of the United States’ bicentennial, the excitement was in the air, and the unique bout between the greatest boxer of all time and a skilled grappling legend from Japan was creating quite a buzz. But the prevailing view of the media and the fans was that it would be a “fake pro wrestling match.”

Nonetheless, the stage to determine the best fighter in the world was set, even when most didn’t believe the contest was on the up and up.

Convincing the public that the fight was worth watching required a hard sales pitch by Ali. Vince McMahon Sr., working together with founder and promoter of Top Rank, Bob Arum, led the charge in making this fight a mega worldwide event and was instrumental in convincing other wrestling promoters to participate.

Promoters organized wrestling cards around the country and the world and later showed the Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki match on closed-circuit TV. A potential audience of 1.4 billion people in 134 countries could partake in the fight. 150 CCTV locations were in the U.S. alone.

Ringside seats for a standard wrestling show at Nippon Budokan were 5,000 yen (roughly $17). However, for the Ali versus Inoki match, that same price put you in the nosebleeds of the 14,000-seat building. The face value of the most expensive ticket was the equivalent of $4,100 today.

Investing heavily in an event with Inoki’s name was strange because he was practically unknown in the U.S., but Ali was a global brand and the most famous name in sports. Lincoln National Productions Ltd., based in California, was created to promote the match.

At Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, the second Showdown at Shea saw more than 30,000 people witness the comeback of WWF champion Bruno Sammartino two months after fracturing his neck against Stan Hansen.

As a precursor to the Ali versus Inoki fight on CCTV, André The Giant faced scrappy boxer Chuck Wepner, “The Bayonne Bleeder,” in a worked mixed style match at Shea. Wepner lost by countout after André unceremoniously dumped the spirited boxer outside the ring.

Rocky III starring Sylvester Stallone, had a similar scene when Sly went against Thunderlips “The Ultimate Male” Hulk Hogan.

Did you know? The referee for the Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki fight was expert grappler and stunt man “Judo” Gene LeBell. He was one of the few people at the time who had a familiarity with mixed matches, though he had not refereed one before.

On the first televised bout of its kind, LeBell choked out boxer Milo Savage in an event held in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1963. According to media reports, LeBell left him unconscious for twenty minutes. Adding insult to injury, LeBell “accidentally” stepped on Savage’s chest when he walked away victorious.

The crowd was so enraged that a man attempted to stab him after stepping out of the ring.

LeBell knew and worked with Bruce Lee in The Green Hornet series of 1966, with “Judo” Gene teaching the lightning-quick Lee grappling techniques to compliment his Jeet Kune Do.

Last-Minute Rule Changes

Until the contest was officially signed at a ceremony during fight week in Tokyo, the rules of engagement between Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki were scrutinized, producing a heated debate that periled the whole event.

The specter of the regulations continued to loom large hours before the event. The Ali camp was extremely nervous about what Inoki might do, especially since it seemed he wanted to do anything he could.

In the final revision of the rules, the change that mainly affected Inoki stated: Kicking is mostly prohibited and would be declared a foul unless the person delivering the blow was kneeling, squatting, or operating down on the canvas.

Takedowns were allowed, but once Ali touched the ropes, there had to be a break.

Leg holds were prohibited, but leg sweeps, leg whips, and leg pulls were allowed only with the shins, the top, or the side of the foot. Palm or heel strikes by Inoki were okay, but not below the belt, Adam’s apple, or groin. Blows to many other body parts were prohibited, and neither fighter could knee or elbow.

At the signing ceremony, Inoki expressed disgust with the rules that seemed to protect Ali and give him an advantage but said he would accept them as negotiated and move forward with the contest.

If given a chance to watch the whole match, you can see that whenever Inoki tried to do anything outside of the restrictive rules, Ali’s corner cried foul, demanding a deduction of points while yelling obscenities to referee Gene LeBell.

Great Anticipation

The fight finally arrived on June 26th, 1976, but it turned into a rather tepid and uneventful affair. We had Mayweather versus McGregor; the ’70s got Ali versus Inoki.

After months of hype and trash-talking amongst both parties, Muhammad Ali was unable to send “Inoki to meet his ancestors,” Inoki didn’t impress too many fans by adopting a crab-like position now known as the “butt-scoot” throughout most of the contest.

During the first couple of seconds of the first round, Inoki launched himself toward Ali with a scary flying kick. Inoki then “butt scooted” on the mat like a crab trying to kick Ali in the legs. Ali landed only six punches and spent most of the fight goading Inoki to “Get up off the floor and fight like a man!”

Naturally, Inoki invited Ali to grapple with him on the mat instead. With both at a standstill, Ali took over 100 kicks of varying force to his legs.

It almost seemed like people would have preferred if the match had been a work. At least if it were, it would have had the potential to be more entertaining than the dreadful contest they had to suffer through.

By the altercation’s end, both frustrated fighters embraced and awaited the judge’s decision. People usually boo at live events, but people who paid to watch this debacle in different CCTV locations became unruly, with many not even watching until the end.

Did the Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki Match Live up to Its Expectations?

“The War of the Worlds” failed to live up to its lofty expectations. The lack of action drew sharp criticisms from fans and the media. Trash rained from the Nippon Budokan cheap seats, accompanied by cries of “Money back!” “Money back!” in broken English.

The referee of the match, Gene LeBell, said, “I didn’t think in that fight either of them actually got to show their true ability. They were both much better competitors than they showed that night. But it was the first big mixed martial arts fight. It’ll go down in history as that.”

The next day, the Japanese press scorned Inoki to the point that he didn’t want to go outside. The encounter was now labeled “The Rip-Off of the Century.”

Judge Kokichi Endo, who wrestled as a tag-team partner with Rikidozan, scored the fight 74-72 in Ali’s favor. Boxing judge Kou Toyama determined that Inoki deserved the win and scored 72-68 for Inoki.

Referee/judge Gene LeBell had the final say and could determine the winner. He considered the points he penalized the wrestler for some illegal blows and scored 71-71, which made it a split draw.

“A lot of people thought Inoki had more kicks. I judged the fight not based on how many jabs or kicks were thrown. I judged based on damage done,” explained LaBell.

“I could throw one hook and throw a guy into the nickel seats, and throw seventeen jabs and not do any damage. What and who did the most damage? I called it a tie. Both of them did the same amount of damage.”

Aftermath and The Damage to Muhammad Ali’s Legs

Media and pop culture positioned flashy television and film-friendly styles like karate, taekwondo, and kung fu as accurate representations of martial arts. But in a real fight, you “do whatever works.”

Certainly, Inoki scooting on his butt in a crab-like manner wasn’t exactly thrilling for the fans, but his technique was smart and mostly neutralized Ali’s punches. But the boxer took this as Inoki being scared to face him.

Ali later admitted his surprise with Inoki’s strategy because he expected Inoki “to rassle,” but also derided Inoki’s tactic.

“I wish the fight was better, but I did my best according to the conditions,” Ali said.

“I’ve never fought a man who fought on the floor, and I can’t fight my style with a man who stays on the floor. He showed fear respecting my punching ability. I think I won, just the mere fact of him not fighting. I stood up and tried to fight. I was the aggressor; he wasn’t. He fights like a coward.”

Didn’t the constraining rules imposed by Ali’s people obligate Inoki to use such an unconventional strategy? Did he think Inoki wanted to scoot around on his behind the whole match?

New York Times Tokyo Bureau Chief Andrew Malcolm got an exclusive interview with Ali in the dressing room.

Ali continued his rant by saying, “[It proves] boxers are so superior to rasslers. Inoki didn’t stand up and fight like a man. If he had gotten into hittin’ range, I’d a burned him but good.”

Ali hadn’t even worn a mouthpiece; such was their expectation that he wouldn’t be touched. Other than Inoki’s illegal elbow in the sixth round, while the two were tied up, Ali’s face went unscathed. But the same couldn’t be said about his legs.

Amongst Ali’s sizable entourage was Jhoon Rhee, known as the “Father of American Taekwondo,” who helped Ali train for his fight against Inoki. When Rhee pinpointed Inoki’s strategy, he advised Ali to block the constant low kicks launched by the wrestler. This tip probably saved Ali from more severe or irreparable damage to his legs.

Most of Inoki’s kicks were not devastating, but the sheer number of targeted strikes to areas Ali was unaccustomed to being struck took its toll on the champion boxer.

Weeks before the bout, the Korean government contacted Jhoon Rhee, and he, in turn, practically begged Ali to visit Seoul. When Ali agreed to something, he’d generally follow through. But this trip was against his doctor’s advice, and a day after suffering significant damage to his legs.

Publicist Bobby Goodman who’d worked with Ali for many fights since 1963, remembers the seriousness of Ali’s injuries.

“His legs were so swollen he couldn’t put his pants on. It was awful. It was just grotesque. I think Inoki broke every vessel in Ali’s legs. He was in such pain. Ali tried to minimize everything. ‘It’ll be okay. I’ll be fine.’ But it was definitely not fine. Black and blue wasn’t a fair description.”

Trainer Angelo Dundee was highly concerned, knowing the rubber match between Muhammad Ali and Ken Norton was a mere three months away. Ali’s physician, Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, thought it was foolish for Ali to fly with the injuries and attempted to persuade him to remain in bed before contemplating boarding a plane.

He then made him aware of the dangers: “If any of those clots get loose and go up into your head, you’re dead. You can die from this. Those knots that are in your leg can get infected and travel. And when they travel, they’ll go right into the lungs, right to the heart, right to the brain.”

Ali made the three-day trip to Korea anyway but was admitted to St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, California, the moment he got back in the States.

According to a United Press International report, Inoki had done some notable damage to his legs. They found superficial clotting near the surface of both knees, severe muscle damage to his left leg, anemia produced by bleeding into the leg from the injury to blood vessels in the muscle, vein damage, and an accumulation of both fluid and blood.

Within a couple of days after being administered blood thinners, Ali showed “substantial progress.”

Muhammad Ali versus Antonio Inoki certainly didn’t live up to the hype, but it opened people’s eyes to the possibility of uniting fighting styles.

Professional grapplers and shooters like Lou Thesz, Karl Gotch, Danny Hodge, Billy Robinson, and “Judo” Gene LeBell helped influence the Japanese proto-MMA scene.

Shootfighting-style wrestling companies in Japan like UWF, Shooto, UWF-International, RINGS, Fujiwara Gumi, and Pancrase emerged. Pancrase (from the word Pankration, a fighting sport in ancient Olympic games) was formed by two former Antonio Inoki students: Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki.

Later we saw the birth of MMA companies like Pride, K-1, and UFC (who eventually acquired Pride), which in 2019 had nearly $1 billion in revenue.

“I think the Ali-Inoki show was a successful event, except for the fight itself was a failure,” Pride executive Hideki Yamamoto once said.

Antonio Inoki continued at the helm of New Japan Pro Wrestling, participating in mixed style matches, and was even given the WWF Martial Arts Title.

He appeared in the 1978 film The Bad News Bears Go To Japan, and after wrestling, he went into politics. He continues to be a national hero to all Japanese people, where most understand that the rules imposed on him in the match against Ali severely limited what he could do against the world-famous boxer.

To learn much more about this fascinating event, you can purchase Ali vs. Inoki: The Forgotten Fight That Inspired Mixed Martial Arts And Launched Sports Entertainment by Josh Gross.

These stories may also interest you:

- Andy Kaufman & Jerry Lawler – The Feud That Took Memphis Mainstream

- Andre the Giant and Akira Maeda | How Their Fight Turned REAL in Japan

- 16 Unforgettable Andre the Giant Stories Told By His Friends

Can’t get enough pro wrestling history in your life? Sign up to unlock ten pro wrestling stories curated uniquely for YOU, plus subscriber-exclusive content. A special gift from us awaits after signing up!

Want More? Choose another story!

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, and Flipboard!

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

Pro Wrestling Stories is committed to accurate, unbiased wrestling content rigorously fact-checked and verified by our team of researchers and editors. Any inaccuracies are quickly corrected, with updates timestamped in the article's byline header.

Got a correction, tip, or story idea for Pro Wrestling Stories? Contact us! Learn about our editorial standards here. Ever wanted to learn more about the people behind Pro Wrestling Stories? Meet our team of authors!

ProWrestlingStories.com participates in affiliate marketing programs. This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we may earn commissions at no extra cost to our readers. This supports our mission to deliver free content for you to enjoy!