Before Randy Poffo changed the wrestling world as “Macho Man” Randy Savage, he was a talented baseball player with big-league aspirations. This is the story of his first love and how his journey led to him becoming a budding star with the largest wrestling company in the world.

Quick Tip for Facebook Readers

Many of our readers connect with our content through our Facebook page. However, Meta's built-in browser (which opens by default on mobile) occasionally freezes mid-article- a known issue unrelated to our site. To enjoy uninterrupted reading: Tap the three dots in the top right corner → Select 'Open in external browser.' This will resolve the glitch. Thanks for your support. We want your wrestling stories to stay as smooth as a top-rope hurricanrana!

Before There Was Wrestling and a Randy Savage, There Was Baseball for Randy Poffo

Angelo Poffo was the type of dad who would do anything he could to support one of his children when they expressed a new interest in something. When Lanny voiced an interest in the violin, Angelo immediately bought his youngest son an imitation Stradivarius. Later, when Lanny mentioned photography, Angelo purchased a high-end Nikon camera with multiple lenses and other accessories while setting him up with a dark room. Angelo even went as far as asking fellow wrestler and tag team partner Killer Kowalski for suggestions on what equipment to buy.

Lanny and big brother Randy Poffo (Savage) also shared an interest in baseball. Angelo again put full support behind his boys by having a winterized batting cage with a pitching machine built in their yard, so the brothers could keep their skills sharp while escaping the nasty Midwest winters that annually hit this suburb 20 miles west of Chicago. Angelo also fed their love of the game by frequently bringing the Poffo brothers to either Comiskey Park or Wrigley Field to watch baseball’s stars when they came to play in Chicago.

Both Poffo boys also possessed his athletic DNA. Lanny and Randy Poffo played sports throughout their childhoods – basketball, football, baseball, and wrestling – but baseball truly captured Randy’s heart, oftentimes walking with Lanny to a nearby neighborhood field to play ball. A devout Cubs fan, Randy’s favorite players were Cincinnati’s Pete Rose (a.k.a. Charlie hustle) and Johnny Bench (an all-time great catcher). When Randy was 10, Randy’s mom, Judy Poffo, signed him up for Downers Grove Little League. From the first day, he was a catcher.

Randy Poffo must’ve caught the bug from his dad, as Angelo was a catcher for the DePaul University baseball team. Like Randy, Angelo had dreams of a baseball career, but in 1947, he was knocked unconscious by a high, inside pitch, and try as he might, couldn’t overcome being "plate-shy." Angelo received pro offers before the incident and had signed to report to a North Carolina state league team the next spring but instead turned to his second love – wrestling.

Angelo mentored Randy about the skills and strategies that went along with playing catcher, such as how to call a game, block the plate, see the field, and emulate players like Bench and Randy Hundley.

“What was immediately noteworthy was that Randy threw the ball back to the pitcher with more velocity than the pitcher pitched the ball to Randy,” childhood friend John Guarnaccia told Sports Illustrated in a 2011 interview. “Randy Poffo was definitely the best player in town for his age. There was no doubt about it.”

"I got the chance to play against him in Little League, and he was a beast," added Guarnaccia, who was drafted by the Philadelphia Phillies in a March 2015 interview with The Chicago Tribune. "I’d heard about him and (wanted to pitch around him). He swung on purpose to get another chance to hit me. On the next pitch, he hit a home run over the centerfield fence. He was a driven young man."

In 1968, the Poffo family moved to Hawaii for nearly a year following Randy’s sophomore year at Downers Grove North High. Angelo was offered a lucrative opportunity to wrestle for promoter Ed Francis in the Hawaii territory and Japan. Angelo saw the temporary uprooting as a chance for his boys to focus solely on baseball while being homeschooled.

Lanny said Angelo figured by holding his sons back a year while he wrestled in Hawaii, they would have less of a chance of getting drafted for the Vietnam War, and Randy would have a competitive advantage once his high school baseball career resumed. During the time away, Lanny and Randy Poffo played baseball nonstop. There were never-ending games of catch, followed by more never-ending games of catch.

That time in Hawaii made Randy a different level player,” Lanny Poffo told Sports Illustrated. “It helped us both develop in big ways.”

When Randy returned to Downers Grove North High School, he was one of the oldest students in his grade, if not the oldest. He was also a much more polished baseball player, and the results showed on the field and the boxscore.

Randy Savage Breaks State Baseball Records

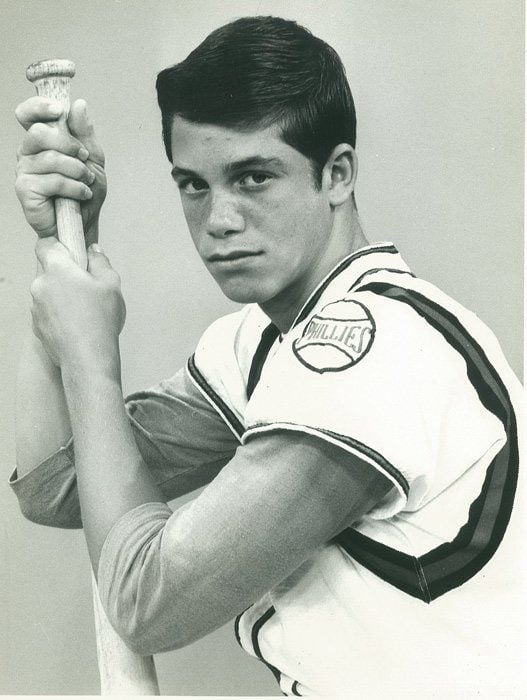

During his junior season, Randy Poffo was named his team’s Most Valuable Player after posting a .500 batting average, tops among all Chicago high school hitters, with three home runs, four triples, and eight doubles. The switch-hitting catcher was also named to the All-State Team.

His senior season was even better as Randy Poffo batted a state record .525 when his team was the Western Suburban Conference co-champion. Randy again was named team MVP and selected to the All-State Team. In addition to excellence on the diamond, Randy also played football as an outside linebacker and basketball and was a National Honor Society member. However, his excellence in baseball made his dream of becoming a Major League Baseball player seem possible.

The stands were dotted with major league scouts who attended games watch Randy Poffo play during his senior season to gauge his value as a prospect for the upcoming 1971 MLB Draft. Guarnaccia recalled a day scouts came to see Savage play, and he was sick with a 102-degree fever. After struggling that game, scouts came around less often.

"I heard one scout say he over-hustled too much, which is BS," Guarnaccia said.

Randy wasn’t selected in the 1971 MLB Draft, and Lanny said his brother turned down a scholarship offer from Arizona State, one of the top collegiate baseball programs in the country. “That was the darkest of dark times for us,” Lanny told Sports Illustrated. “To describe it simply as sad does the pain no justice. Randy was ignored. Completely ignored. I assure you, he never forgot that feeling.

“Never.”

In 1970, Randy also played with the Chicago Orioles, a top amateur team comprised of local high school and college all-stars. He was set to play with them again after his senior season until his pro aspirations were revived.

The St. Louis Cardinals hosted a free-agent tryout at Busch Stadium, so Randy shook off the devastation of not being drafted and, with his dad, drove 300 miles to participate. Out of the more than 200 players who attended, Randy was the only one who received a contract offer. Randy signed with St. Louis on the same day as future five-time MLB All-Star first baseman Keith Hernandez.

"(The Cardinals) were really surprised I wasn’t drafted," an 18-year old Randy Poffo told the Downers Grove Reporter the following week. "They felt I had unlimited potential, but it doesn’t matter now. The door is open now, and I’ve got my chance. You can’t bring your contract to spring training, only your bat."

Randy Poffo began his professional career in the Fall of 1971 with the Cardinals’ Gulf Coast League team – the Sarasota Red Birds. There, he suited up with future major league outfielders Jerry Mumphrey, Mike Vail, and Larry Herndon.

Motivated by the chip on his shoulder after going undrafted, Randy quickly established a reputation for his work ethic, usually staying late after workouts and games to run the outfield and practice throwing from behind home plate down to second.

Herndon said Randy Poffo was well-liked by teammates and described him as a diligent worker. “He kept everybody [on the team] loose,” Herndon told ESPN. “He was always having fun.”

Herndon said Poffo used to swing a bat into a car tire fixed to a tree as a regular training exercise to strengthen his hands and make sure he utilized his legs during swings. The technique was so effective that Herndon adopted it from Poffo when he became a manager.

The hard work paid off as Randy Poffo was named an all-star as a catcher after batting .286 (tops among all regulars) with a team-high two home runs (the ballparks were huge), a .492 slugging percentage, and no errors in 15 games behind the plate.

Randy excelled during his second professional season, again in Sarasota, batting .274 in 52 games with a team-high three home runs and another selection to the All-Star Team, this time as a switch-hitting outfielder.

"He was a heck of a hitter," said Tony Garofalo, a former longtime trainer who trained with Poffo while serving the 1972 Gulf Coast League Cardinals in the same capacity. "He wasn’t a five-tool baseball player. He could hit, he could field, he could run a little bit, but he couldn’t throw very well. He had a funky throwing motion. He would’ve been a great DH (designated hitter)."

"I had kind of a scatter arm," Randy said. "My throws to second would tail to the outfield, sometimes right field."

Garofalo lived with Randy and two other players in a place on the beach in Sarasota. He didn’t know anything about Randy’s childhood or what his family did for a living.

"It wasn’t until Angelo and Lanny visited him that they found out. "I asked, ‘Do you want to do that?’ Randy said, ‘I don’t know. I’m going to play baseball.’"

Getting Involved in Wrestling

While teammates like Mumphrey and Vail made comfortable salaries thanks to the contracts they signed as highly touted prospects, Randy fought to survive on $500 a month. While he lacked the same financial comfort, he used his Honor Society smarts in a way to be resourceful to compensate for his low compensation.

"That’s not a lot of money, so my father promised him that he would subsidize him, but he didn’t need it," Lanny said. “You wouldn’t believe how much money Randy made in the minors from playing cards. He’d make sure to play with all the bonus babies, and he’d take them to the cleaners. Was he the best baseball player? No. But he had a brain like a razor blade — very sharp. I always said Randy belonged on ESPN with the poker players.”

Randy began 1973 with Sarasota for a third season. He struggled early on, but then, just when it appeared he might lose his roster spot, his bat came alive, and Randy raised his batting average to .344 through 25 games. His surge at the plate caught the Cardinals organization’s attention, and they promoted him to Class A Orangeburg of the Western Carolinas League. There, he played for manager Jimmy Piersall, an eccentric former major leaguer who famously ran the bases backward after hitting his 100th career home run.

The club was an independent team but featured several players from the Cardinals organization. Randy was assigned to room with a young outfielder named Tito Landrum, who would play nine major league seasons. During this season, the first inkling about Randy’s intention to eventually follow in the family business and become a professional wrestler was evident.

"Randy Poffo was a very aggressive player and was well-liked on the team because of that aggressiveness," Landrum told The Baltimore Sun in a June 1994 interview. "Unfortunately, much like the rest of us, he had a problem hitting the curve.

"But his intensity is real. I can remember him setting up a ring in the locker room and wrestling with the guys. He told us he was going to be a wrestler someday."

Randy was highly regarded but slumped and batted .250 in 116 games and showed very little that he was a legitimate major league prospect. In Sarasota, Randy was a starter, but in Orangeburg, he found himself either on the bench or spelling others at catcher or first.

A highlight came late in the season when Guarnaccia, a fourth-round draft pick of the Phillies now playing for Spartanburg, stepped up to the plate while Randy was catching. The two smiled at each other — childhood friends from suburban Chicago, reunited in a gnat-infested minor league stadium.

“When I got up there, Randy looked at me and said, ‘I’ll tell you what pitches are coming.’ And he did,” Guarnaccia says. “That was just loyalty to a friend. Nothing more.”

The nightmare continued as Randy’s season concluded shortly thereafter when he separated his right shoulder and tore the muscles after colliding with the catcher at full force on a close play at home plate. Two weeks before Christmas, Randy received a letter telling him the Cardinals released him.

“That was hard for Randy,” Lanny said. “I don’t think he took it well because he saw it as perhaps the end of the road.”

Randy moved from Illinois back to Sarasota to be around ballplayers and began pestering scouts to give him a chance. "But nobody wanted to give me a chance," Randy said. "They were cutting players because teams were being cut back, and then there was the energy crisis. But, I was still not dejected."

Randy attended a Cincinnati Reds tryout camp at Lowry Park in Tampa, and area scout supervisor George Zuraw of Englewood invited him to spring training before the 1974 season. He hit six home runs, four left-handed and two right-handed. On the final day of camp, he hit a pair of home runs against the Mets.

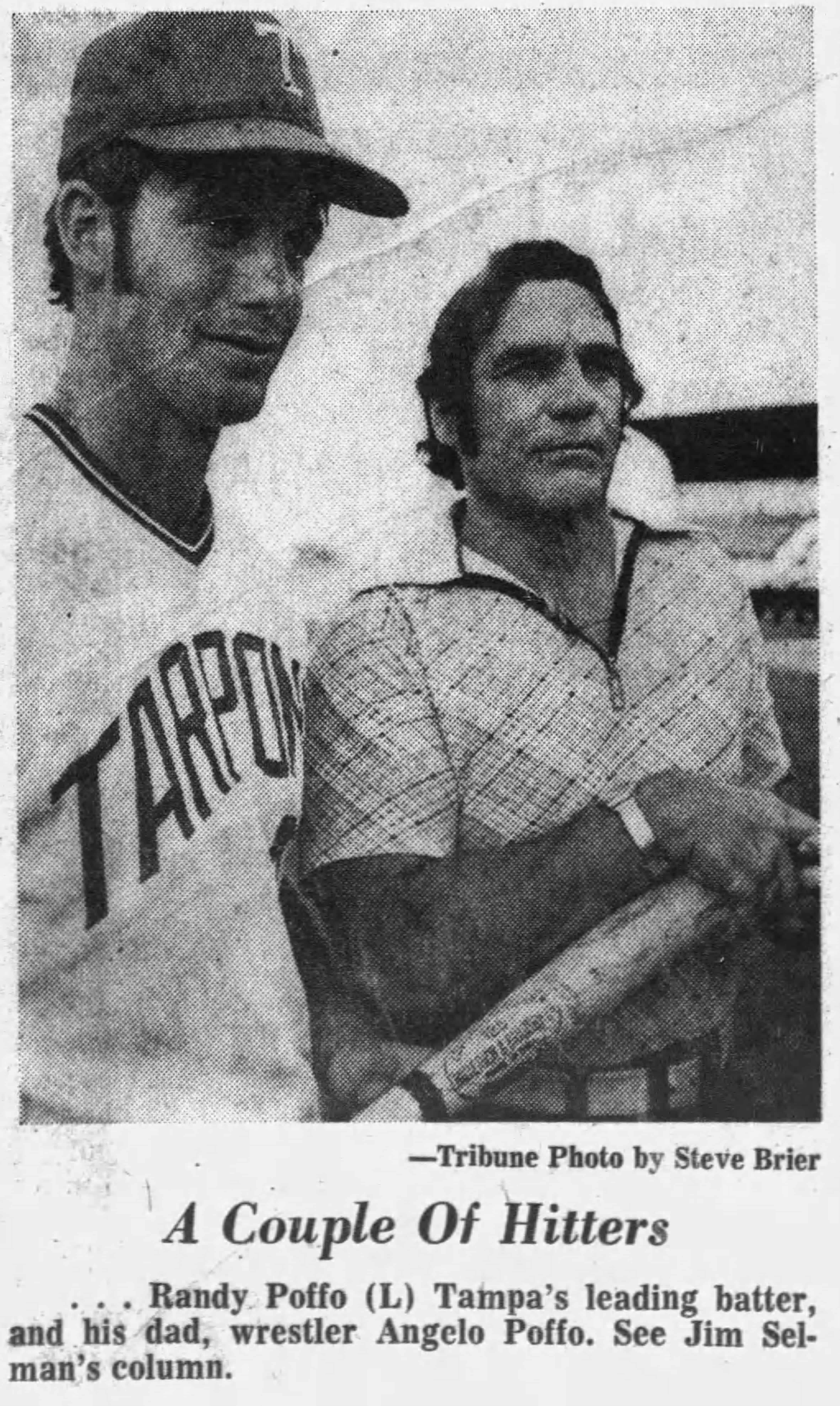

The Florida State League had recently decided to employ the designated hitter rule, and that was the break Randy needed, as manager Russ Nixon said he could use his bat. There was one last chance. With a vacant spot on their Class A Florida State League club, the Cincinnati Reds signed Randy Poffo and assigned him to the Tampa Tarpons.

"I said let him swing the bat here," Nixon recalled. "He is that type of hitter. He wants to play. He has the greatest desire of any kid I ever saw. He is an aggressive hitter."

"Randy Poffo was a super athlete," Pete Rose told Sports Illustrated. Rose was a spring-training teammate of Randy in 1974. "He was very limber, flexible, so it didn’t surprise me; he was a pretty good baseball player."

Randy delivered at the plate and led the division with nine home runs and was hitting near .300 when he dove for a ball in the outfield and broke the forefinger on his left hand.

"I was getting a good chance with them, and I was going all out," Randy said in the March 6, 1975 edition of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. “I had been released once, and if you get a second chance, you’re always fearful it may happen again."

It did, unfortunately. Randy tried to come back too soon from the injury. He was used as a designated hitter, but the finger hampered him. He didn’t complain because he didn’t want to lose his job. His average dropped, and his eagerness is what probably cost him his job.

"I got my annual Christmas letter," Randy said.

Although he only batted .232 in 131 games, he finished third in the Florida State League with nine home runs, just behind Hall of Famer Eddie Murray and major leaguer Gary Roenicke, with a team-high 66 RBI. After being released again and realizing his throwing arm wasn’t considered strong or accurate enough to play in Major League Baseball, Randy took the idea of changing his throwing arm very seriously.

“Honestly, he didn’t have the talent to go any farther,” says Mike Moore, who was the Tarpons’ general manager and later became the president of Minor League Baseball. “He just didn’t. But I’ll never forget this — one day [manager] Russ Nixon and I got to the stadium at 1 in the afternoon, and I peeked out onto the field and saw these baseballs flying across the diamond. Randy (a natural right-hander) was all alone, with a bucket of balls, standing in center and throwing them one by one to home plate, all with his left hand. I said, ‘Randy, what are you doing?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Trying to make myself more valuable.’ He was that type of guy.”

Throwing with his off-hand was something Randy first started in high school when he practiced pitching with his left hand again to increase his value. He resumed the practice while rehabbing his shoulder injury, throwing 1,500 balls against a wall per day.

"I wasn’t naturally ambidextrous, but I taught myself to throw left-handed," Randy said. "I guess persistence was my best attribute. I felt if I can do that, I can do anything."

"I’d throw for two hours a day," he continued. "I’d go in Payne Park and throw against that wall every day. I saw it was improving. I even made myself eat lefthanded in disciplining myself.

"I went out and paid $30 for a lefthander’s glove last August when I was still with the Reds. At the time, I thought I was an idiot for spending the money like that. In fact, I ordered it through my manager and didn’t even say it was for me. I said it was for a good friend of mine. I didn’t want him to think I was goofy."

![Randy Savage | The Forgotten Baseball Career of Randy Poffo News clipping on how Randy Poffo lifted the Tampa Tarpons out of a 5-game losing streak over the Winter Haven Red Sox [The Tampa Tribune, Tuesday, Jul 9, 1974]](https://prowrestlingstories.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/The_Tampa_Tribune_Tue__Jul_9__1974_.jpg)

“Fight on the Diamond!” How Randy Poffo Received the Nickname “Macho Man”

This season also saw Randy earn a nickname that would stick with him for the rest of his life. On April 29, 1974, midway through a game against the Winter Haven Red Sox, Randy was preparing to bat when Rac Slider, the opposing manager, signaled for a pitching change. Randy was kneeling in the on-deck circle waiting for the inning to begin when he was beaned by a warmup pitch from the opposing pitcher, Joe Keener, setting off a monstrous brawl.

“So the pitcher just rears back and drills Randy in the helmet,” says Don Werner, a Tampa catcher. “Randy charged the mound and started fighting the guy. We were all wondering what in the world he was doing.”

"I guess he thought I was looking at his pitches, and the next thing I knew, he had hit me in the face," Randy said. "I just ran out there by instinct and attacked him, worked him over real good.

"Next day in the paper, some writer gets on me, says I was acting like some macho man. I liked that, and it became part of my name.

"Some fans put a banner up in the outfield that said ‘Hit it here, Macho Man,’ " he said. "I kind of dug that. It was perfect for me."

A version of the incident from the Apr. 30, 1974 edition of The Tampa Tribune by Assistant Sports Editor Jim Selman differed about the brawl itself but not the fact that Randy was intentionally thrown at.

"Right-hander Joe Keener struck Randy Poffo on the batting helmet while he was waiting close by to open Tampa’s half of the second inning. Poffo suffered a lump on the back of his head – he turned his face just before the ball hit him. He continued to play, but only after attempting to charge the mound. Plate umpire Parker Lerew restrained him until Manager Russ Nixon, and trainer Jack Muenchen got Poffo quieted down. The benches emptied, and it seemed for a few minutes that there would be real trouble. Muenchen quoted Poffo as saying Keener was looking directly at him when he threw."

While Randy was clinging to the final hopes of achieving his major league dreams, the reality was setting in, and the pull toward a career in professional wrestling grew stronger. Randy said he and his Tampa teammates would go and watch wrestling after Friday night games.

![Randy Savage | The Forgotten Baseball Career of Randy Poffo Box score from the very game Randy Poffo attacked the pitcher after getting beamed in the helmet while waiting in the on-deck circle [Tuesday, April 30, 1974 edition of The Tampa Tribune]](https://prowrestlingstories.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/The_Tampa_Tribune_Tue__Apr_30__1974_.jpg)

"I remember the first time I saw him," Jerry Brisco told The Miami News in a May 1986 interview. "It was around 1974, in the old Fort Myers Armory. He had good arms, but he was small. He had to keep his weight around 175 pounds because of baseball, and that’s pretty little for the ring. But it didn’t stop him. The main thing I remember is that he had a cocky attitude once he crawled through the ropes."

Realizing he was near the end of his baseball career, Randy wanted to take one more shot at achieving his dream before he could commit to a career in wrestling with the peace of mind that he exhausted every opportunity to play baseball. He wrote letters to numerous clubs but didn’t sell himself as a right-turned-lefty. He didn’t want to be seen as a gimmick – ironic given how he later became successful in wrestling.

The hard work paid off as the San Francisco Giants said Randy could attend their camp, but it was in Casa Grande, Arizona, and it would be at his expense. Then, at the 11th hour, on Mar. 24, 1975, Randy signed with the Chicago White Sox and tried to earn a roster spot with one of their minor league teams as a left-handed first baseman.

"I have to say we were impressed by his ambition and determination," White Sox Farm Director C.V. Davis said in the March 25, 1975 edition of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. "We’ll take a chance on him in spring training, but didn’t guarantee him anything. I understand he is a good hitter."

Poffo attracted much attention during spring training with his ambidextrousness and surprised White Sox Manager Chuck Tanner. Still, he hadn’t mastered the vital sidearm throw from first to second on double plays. He failed to make the final cut for a place in the Chicago minor league system with the Appleton club in the Midwest League or their AA team in Knoxville.

"When they walked up and took my uniform out of my locker, I couldn’t believe it," Randy said. "It got me pretty worked up, and finally, I told ‘em if I couldn’t play baseball, maybe no one else would either. I told them I just might have to burn down the clubhouse and grandstands."

Upon his release, Randy’s undeniable spirit was on full display as he picked up his equipment, walked through the clubhouse door, and, as teammates looked on, systematically splintered each of his bats against a nearby tree.

The baseball dream had come to an end, but as one door closed, another one opened. It was then when 24-year old Randy Poffo followed his dad Angelo and 22-year-old brother Lanny into the family business – and became the first pro baseball player to become a wrestler.

"Randy Poffo was a real nice guy," former Cardinals player development director Lee Thomas said, but then the manager of another rookie league team. "He seemed like such a quiet guy at the time.

"He was a good athlete, but you could tell he wasn’t going to go too far in baseball. He was a mediocre catcher, but every now and then, he’d show you a little bit with the bat.

"We knew he was moving on to something else; we didn’t know what."

Poffo called promoter Francis Flessner in Detroit when the White Sox released him, and Flessner agreed to give him a chance. He defeated Joe Banic in his official wrestling debut as Randy Poffo and wrestled there for six months.

"I love baseball, but I kept hearing about my brother and dad doing so great. I just wanted to get into it," Randy said in a Nov. 1975 interview with The Tampa Tribune. "You never get as much satisfaction out of baseball as you do wrestling. You take all your frustrations out in wrestling. In baseball, some skinny guy on the mound may get you out, or maybe you hit a couple of line drives that are caught, and you go home 0-for-4.

"No matter what my background, I couldn’t have gone into wrestling when I got out of high school. I was too small. Wrestling may have been my first love, but baseball looked more practical for my future."

Randy wrestled with his brother in the family-owned promotion IWA and Memphis territory while working out with the same fervor he showed on the baseball field and bulked up to 225 pounds. Fans took to his intensity and athleticism, and Randy became a main eventer.

In 1985, Randy Poffo made his WWF debut, and the Macho Man went from a big fish in smaller ponds to a budding star with the largest wrestling company in the world. Randy was typically a middle-of-the-lineup hitter in minor league baseball, but the most he ever earned was $800 a month. During the first year of what would become a Hall of Fame career with the WWF, he earned almost $500,000.

"The way I explain it sometimes is like this: I wasn’t a bonus baby," Savage told The Chicago Tribune, Aug. 14, 1988 edition. "I bounced around the minors in baseball, and I bounced around in the minors of wrestling too, before I got called up by the WWF. If I have one major attribute, it’s my drive."

Despite his new, successful career in wrestling, Savage kept baseball in his life. He frequently attended major-league games while talking to many players who sought him out and threw out the first pitch for a Detroit Tigers game in 1993. He also did guest commentary and appeared on game broadcasts for interviews multiple times. One appearance occurred on Sept. 21, 1989, during the third inning of a Cincinnati Reds game that is a part of baseball and wrestling folklore. While in the press box for a radio interview to promote a TV taping for Saturday Night’s Main Event at nearby Riverfront Coliseum with Reds play-by-play voice and avid WWF fan, Marty Brennaman, Macho Man, unfortunately, became the center of attention leading to his ejection by team owner Marge Schott, who believed he was a distraction. Hall of Fame baseball writer Hal McCoy reported on the incident for the Dayton Daily News:

"The Reds saluted him from their dugout and (outfielder) Eric Davis flexed his muscles. All four umpires gathered near the pitcher’s mound to look into the booth. Fans turned and waved. Schott, though, sent a message through her nephew, Executive Vice President Steve Schott, who relayed the message through radio producer Doug Kidd. ‘Schott says if you ever want to go on the air for the Reds again, get him off the air.’

The Reds went on to lose their 10th consecutive game.

While Savage made his name in the ring, his time on the diamond is remembered back home. A plaque honoring Randy Poffo hangs with more than 60 others in a hallway of North Downers Grove North High School, near the gym door closest to the athletic department’s office, second row down from the ceiling.

Listen to the late Lanny Poffo talk about the baseball career of his brother, Randy Savage:

If you liked this piece, be sure to check out these recommended articles:

- Remembering My Brother Randy Savage on His Birthday

- Randy Savage – "The Final Promo" | Was It Leading to WWE Return?

- Macho Man Randy Savage Ruins a Feel-Good Moment at Waffle House

Can’t get enough pro wrestling history in your life? Sign up to unlock ten pro wrestling stories curated uniquely for YOU, plus subscriber-exclusive content. A special gift from us awaits after signing up!

Want More? Choose another story!

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, and Flipboard!

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

Pro Wrestling Stories is committed to accurate, unbiased wrestling content rigorously fact-checked and verified by our team of researchers and editors. Any inaccuracies are quickly corrected, with updates timestamped in the article's byline header.

Got a correction, tip, or story idea for Pro Wrestling Stories? Contact us! Learn about our editorial standards here. Ever wanted to learn more about the people behind Pro Wrestling Stories? Meet our team of authors!

ProWrestlingStories.com participates in affiliate marketing programs. This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we may earn commissions at no extra cost to our readers. This supports our mission to deliver free content for you to enjoy!