Like so much of the sweet corn and wheat that lines the green belt between St. Louis and her sister city, Kansas City has been a sweet spot for professional wrestling. A litany of formidable talent flourished in that area, making Heart of America Sports Attractions, later known as Central States Wrestling, a territory worth exploring.

It was one of the original territories of the National Wrestling Alliance, with two of the NWA’s six "founding fathers" promoting it. Often referred to simply as "Kansas City," the territory thrived until 1989 when it met its unfortunate demise.

Quick Tip for Facebook Readers

Many of our readers connect with our content through our Facebook page. However, Meta's built-in browser (which opens by default on mobile) occasionally freezes mid-article- a known issue unrelated to our site. To enjoy uninterrupted reading: Tap the three dots in the top right corner → Select 'Open in external browser.' This will resolve the glitch. Thanks for your support. We want your wrestling stories to stay as smooth as a top-rope hurricanrana!

Jim Phillips, author of this article and one of the great wrestling historians here at Pro Wrestling Stories, is in the challenge of his life after being paralyzed on January 21st, 2023. Learn his story and how you can help him reach his goal of taking his first steps again!

Welcome back, wrestling fans, to another edition of the Wrestling Territories. Our last stop saw us traveling through World Wrestling Association in Indianapolis, a small, center-of-the-country promotion whose impact was felt coast to coast. Fasten your belts as we take a seven-hour journey west along route I-70 to the home of vast prairies, rolling hills, and natural beauty, and pay a visit to Heart of America Sports Attractions, later known as Central States Wrestling!

Rise and Fall of NWA Central States Wrestling (CWA)

The origins of the NWA’s Central States Wrestling territory go back to the regional promotion of the Midwest Wrestling Association, which officially joined the NWA in 1948. The local promoter saw the power that the governing body held, and it was a no-brainer to get on board.

Once involved, the territory saw one of its own become the first recognized NWA Heavyweight champion in Orville Brown. But, the mind behind it all was one Paul "Pinkie" George.

Pinkie George

Born in the winter of 1905, Paul Georgeacopoulos took to the ringed sports in his teenage years as an up-and-coming boxer, but it didn’t work out as he would have liked.

After 160 bouts of varying success, the flyweight caught an ugly knock-out and decided that his love for the business would be best served in the office and not the ring.

Moving to Iowa, he took the promotional end of the sporting world. He promoted basketball briefly in 1948, but that venture fell through, and he returned to what he knew; combat sports.

Sam Muchnick took the reins in June of that year. Pinkie continued as a promoter and ran shows in his Iowa territory to much success.

Orville Brown

Long before the days of sell-outs in Kemper Arena came a thick-chested young scrapper from Sharon, Kansas, named Orville Brown.

Brown was born in the spring of 1908 and was raised a rough-and-tumble farm boy. Due to needing to help around the homestead, he only went to first grade.

Ernest Brown, who had managed wrestlers, first noticed him and convinced him to try his hand at it. Orville took to his training and got enough of a reputation in Kansas that he started to wrestle professionally.

Wrestling exhibitions were held in smoke-filled rooms above bars or a tent at the end of barkers and freaks in a traveling carnival.

It wasn’t long before he caught the attention of St. Louis promoter Tom Packs, who brought him to the professional wrestling hub on the mighty Mississippi. He had several matches of note, including facing former world champion Ed "Strangler" Lewis.

He traveled to Kansas City and into the hands of promoter George Simpson at the Midwest Wrestling Association. Here, he would find a permanent base of operations and claim the coveted Heavyweight Championship, a record-setting eleven times over the next eight years.

He was recognized as the first NWA Champion in 1948 when the MWA was one of the first promotions to adopt affiliation with the nationwide organization.

Unfortunately, Brown was forced to relinquish the title to Lou Thesz following a car crash that left him with career-ending injuries and forced retirement. However, he would not only manage Thesz after that but promote the MWA for the next decade.

Sonny Myers

Sometimes the men who built the foundations of the wrestling business slip through the cracks of history. Another of these homegrown and relatively unsung greats was Sonny Myers.

Born in muggy Savannah, Missouri, in the summer of 1924, Sonny was taken out of school after only completing the first grade.

It wasn’t uncommon in those days for parents to opt for the free labor of their children at the sacrifice of formal education. So he grew up working on the family farm.

Local wrestling promoter Gus Karras saw him playing basketball at the YMCA, and the wily promoter instantly saw money in the agile six-foot-two, nineteen-year-old.

After a short training period in 1944, Sonny had his first match six months later. But, of course, on-the-job training is always best, and Myers cut his teeth and made a name for himself, and bigger matches became available.

He was given a shot at Orville Brown, the MWA Heavyweight Champion. Naturally, he lost, but he proved himself in the eyes of the territory promoters and Brown.

After that, he hit the road to polish his in-ring abilities.

In 1951, Myers went to Texas, one of the hottest areas of the time. But on this night just outside of Houston, in the small town of Angleton, he found out how hot it could get there. He was working for Morris Sigel at the time at the Houston promotion as a heel.

He riled up the crowd so much on that particular evening that he was stabbed by an overzealous fan and had to be rushed to the hospital.

After getting nearly two hundred and seventy stitches to sew the sixteen-and-a-half-inch rip in his abdomen up, he was back on the road.

The trips were long and exhausting in the Friendly State of Texas.

As an example of the life of a wrestler during that time, Myers noted in a magazine interview that after being on the road for 294 days one year, he drove nearly 68,000 miles and paid $3800 in auto repairs. He indeed found out what the wrestling business was all about.

He won the NWA Central States Heavyweight Championship fourteen times between 1951 and 1967. After that, he was only bested by Bulldog Brown, who held the title an extraordinary nineteen times during his run there.

1951 brought much change to the NWA for Pinkie George. Even with Muchnick in the driver’s seat, Pinkie continued to take the conglomerate to new levels.

He incorporated the NWA in Iowa as a non-profit to further solidify the territory.

But with all success come a few hazards to overcome, and as a unified national organization, the NWA started to go in directions that he disagreed with.

The heat between the board members grew to the point that George withdrew later that year. The problems progressed there, culminating in a federal trial in 1958 accusing them of monopolizing the wrestling business.

They weren’t totally wrong in the prosecution. Before Vince McMahon owned it all, the NWA controlled it with a tight grip on influence and how the schedule of the World Champion was set.

With hundreds of amazing Pro Wrestling Stories to dive into, where do you start? Get the inside scoop – join our exclusive community of wrestling fans! Receive 10 hand-picked stories curated just for YOU, exclusive weekly content, and an instant welcome gift when you sign up today!

Harley Race Leads The Way

After 1958, things began to change in The City of Fountains. The MWA was taken over by Bob Geigel and his partners, Gus Karras and New Zealand wrestling talent Pat O’Connor.

He renamed the promotion “Heart of America Sports Attractions” and soldiered on under the NWA banner.

After a failed attempt at using litigation to remain viable in the new enterprise, Pinkie George left the Heart of America.

Not long after, Geigel began his first run as NWA President. During this time, Geigel put all his promotional power and NWA influence behind his local boy, Harley Race, who also had partial ownership in the promotion.

Harley Race was born in 1943, just northwest of St. Louis, in the small town of Quitman, Missouri. He was stricken with polio as a child but overcame the illness.

Unfortunately, this would not be the first time that personal setbacks would test his spirit while he was still a young man; Harley was expelled from high school due to an incident with the principal that left Race kicked in the head and the principal battered and bruised by the strapping young man.

At that crossroads, he decided to follow his love of professional wrestling and make it a career. He grew up on the product that came out of Chicago on the Dumont Network, and he had been doing side work for local promoter Gus Karras for some time.

He was given the duty of "handling" a six-hundred-pound mammoth of a wrestler named Happy Humphrey. Race helped him with his needs and was his regular chauffeur.

At eighteen, he moved to Nashville and began his formal in-ring training.

A few months later, he saw his first gold in the Southern Tag Team Championships wrestling as Jack Long, but the glory was short-lived.

In 1960, he nearly lost his leg in a car crash that claimed the life of his first wife and their unborn son. He was rushed to the hospital and set to have his leg amputated when Karras, who had gotten word of the accident and raced to the hospital, refused to let them take his leg.

It was nearly a year of rehabilitation before he returned to the ring in Texas, where he began a feud with Amarillo’s harbinger of hardcore, Terry Funk. Here, he began to wrestle as Harley Race.

Little did he know how intertwined with professional wrestling history that name would become.

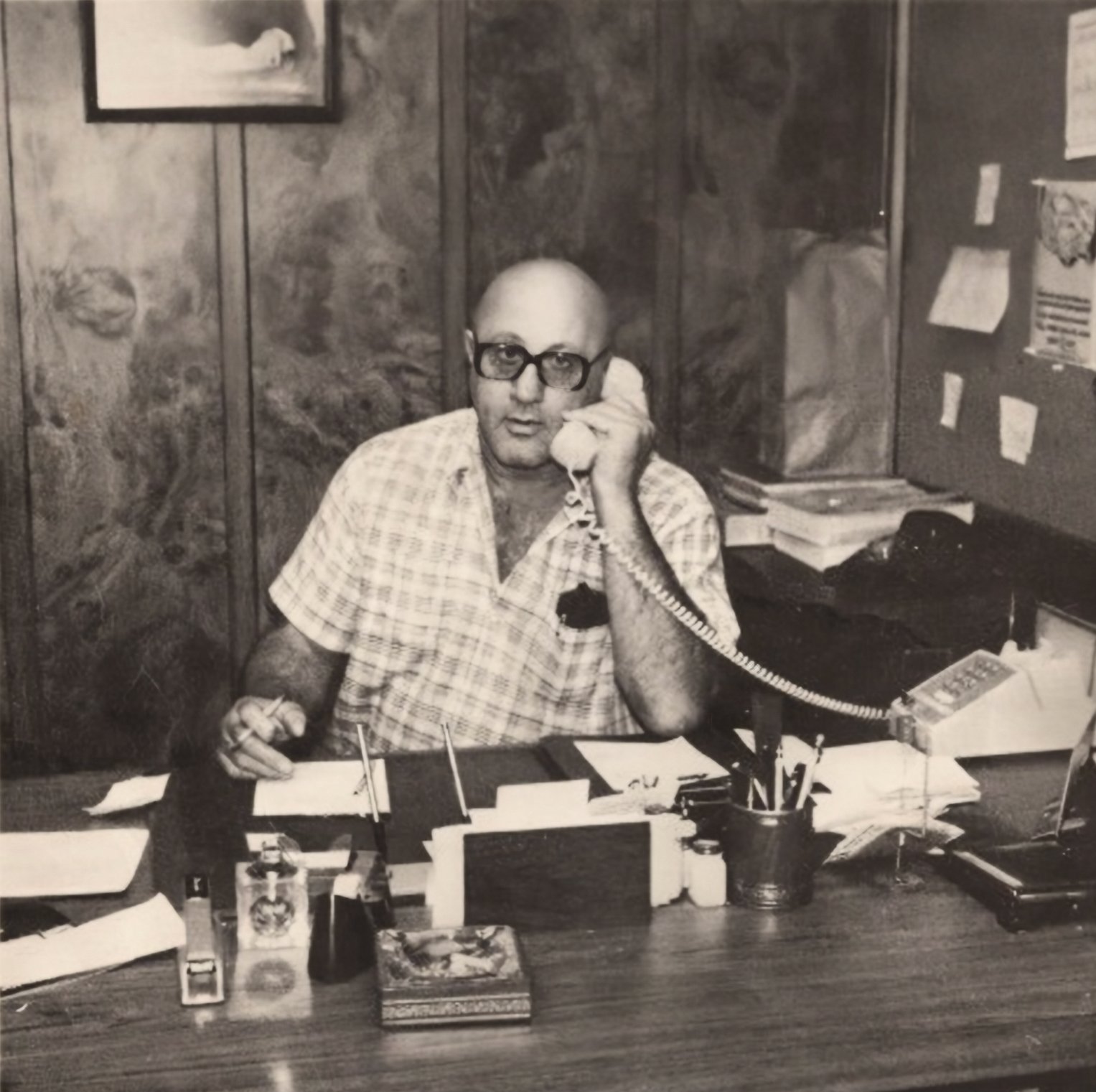

Bob Geigel

It was also in 1963 that Bob Geigel came to be the head of the territory and changed its name to Heart of America Sports.

He and his partners, Pat O’Connor, Gust Karras, and George Simpson, sought to bring more notoriety to the area, growing the territory in the process.

Geigel was eventually moved up the ladder to get a seat on the board of directors of the NWA.

He would take the title of chairman and hold that position for nearly nine years, guiding the NWA into its most prosperous years in the glory days of the ’80s.

The belt, made in secret in Mexico, referred to as the "Ten Pounds of Gold,” was presented to him a few months later by Sam Muchnick.

He had storied feuds with Jack Brisco, Giant Baba, Dusty Rhodes, and Tommy Rich over the next nine years and traded the title back and forth with each of them, giving Baba three title runs in the process.

His uninterrupted title reign at 926 days, while Bob Geigel was serving as NWA President, is only rivaled by those of Lou Thesz, Dory Funk (1563 days), Dan Severn (1479 days), Gene Kiniski (1131 days), and Pat O’Connor (903 days).

The only two wrestlers with more combined time with that title than Race is Lou Thesz, at an astonishing 3,749 days in three title reigns, and Ric Flair, who has 3,116 days across nine times with the belt.

Harley Race held the title for 1,799 days during his "seven times around" as champion and defended it as many as five nights a week in his last run.

This would be his final reign as NWA Champion, and the torch was passed along to Ric Flair at Starrcade ’83 during their grueling steel cage match that goes down as one of the bloodiest and most ferocious of Race’s career.

Bulldog Bob Brown

Working under the nickname of Bulldog, Robert Brown was born in 1938, north of the border in Manitoba, Canada.

He initially worked on the police force and spent some time as a minor league hockey player before turning to professional wrestling in the late ’50s.

He captured his first NWA Central States Wrestling Heavyweight Championship in June of 1968 before heading to NWA All-Star Wrestling in Vancouver, where he worked the hot tag team matches with partner Gene Kiniski.

Brown spent time between the two promotions for the next several years.

Brown worked as a booker for Central States Wrestling and had memorable runs against Harley Race, "Time Keeper" Mike George, a young Ted DiBiase, and Marty Jannety, to name a few. He even dropped the title to Bruiser Brody as Brody stomped through the territory in early 1980.

During his record nineteen times as the Heavyweight Champion in Central States, "Bulldog" Brown faced and defeated many of the top names that came through the territory.

In addition, he had a rivalry that lasted years with his one-time tag team partner and six-time NWA Central States Champion Bob Geigel, who flourished as a promoter there as well.

Brown held his last Heavyweight Championship in Central States Wrestling in 1987.

"Bulldog" Bob Brown worked as a color commentator at Stampede Wrestling after his retirement. He also spent a short time in the WWF wearing the black and white stripes of the third man in the ring.

After suffering from a pair of heart attacks that left him momentarily dead by the laws of man, he was finally revived. He soon worked as a security guard at The Flamingo Floating Casino in Kansas City.

Known as a no-frills and hardened ring veteran that would take on all comers, Brown would march to the ring in his blue trunks and buzzed haircut and work a hard-hitting match every night.

A short story was told about him at his funeral in Kansas City by one of his peers in the business.

“Brown and Geigel were on their way to Wichita to a match once, and suddenly Brown started having a heart attack—I mean, he was dying.

“When they got to Topeka, they were pulled into a hospital, and suddenly, he passed a kidney stone. Then he wrestled."

That’s one tough old pro. But, unfortunately, he died on February 5th, 1997, at the age of fifty-eight, a hell-raiser to the end.

Dewey Robertson

While the name Dewey Robertson may not ring a bell to most wrestling fans, his alter ego resonated with many fans in the ’80s. He became famous in his later years at Mid-South and WCCW as the green-faced, head-butting menace known as “The Missing Link.”

But Dewey Robertson also had a very successful run under his name in the NWA Central States after arriving in 1981. He won every major title the promotion offered while there, beginning with the TV Title in October of that year.

In 1982 the tag titles became the next prize he sought to claim, winning them the first time with partner Rufus R. Jones and later again with "Mr. Electricity," Steve Regal (not to be confused with WWE’s Steven/William Regal), and two times with Hercules Hernandez, of later WWF fame.

Finally, in February, he made his Grand Slam title legacy complete when he beat Manny Fernandez to capture the Central States Wrestling Heavyweight Championship, which he held again after defeating "Bulldog" Brown.

Harley Race took that title from him in June of 1983, and Dewey made his way to the creative pressure cooker of Bill Watts’s Mid-South, where “The Missing Link” was born.

During his time at CSW, though, he left an indelible mark on the promotion.

Later in his career, he overcame his addictions to drugs, alcohol, and steroid abuse. He found healing in his faith and received help from Ted DiBiase and a Christian group in Canada.

He passed away in August 2007 from lung cancer. He was sixty-eight years old.

The Final Days of Central States Wrestling

Bob Geigel sold his Heart Of America Sports Attractions to Jim Crockett Promotions in September of 1986, only to repurchase it six months later with partner George Petraski in another attempt to make a run with the product.

He closed it for good in 1989, and the championship was retired a few months later under its last champion, Akio Sato, who was best known for his WWF run as one-half of The Orient Express with partner Pat Tanaka.

Geigel worked as a security guard in his later years and owned a bar in his beloved Kansas City. He suffered a broken hip in early 2014 and was admitted to a nursing home where onset complications from Alzheimer’s Disease began to surface. He passed away that October at the age of ninety.

Pinkie George never felt that the NWA lived up to the ideals he and the other founders had for it. As the wrestling focus moved to other territories and the Champion’s run became primarily centered in and around the St. Louis area, he felt Muchnick was taking advantage of his seat as President to focus the talent and money in his own backyard.

George continued on his own as an "outlaw," promoting wrestling in direct conflict with the NWA. He passed away at 88 in the fall of 1993. Even though he had tensions with them, he was inducted into their Hall of Fame in 2014, being remembered as the architect of the organization and one of the ones to establish the revered collective.

Harley Race had a career that spanned every major promotion. His run in the WWF in the late ’80s as "King" Harley Race gave us some truly golden moments.

He also worked in Puerto Rico at the WWC and Stampede in Canada and spent some time in Japan before returning to the United States and getting his last big run in WCW.

After getting injured at a house show in his home state of Missouri, he fell out of regular in-ring competition and started building a stable of villains to manage, most notable being Big Van Vader.

In 1999, he started his World League Wrestling in Eldon, Missouri. He has sent many students to Japan and the NOAH wrestling promotion there.

But Race used CSW as his base of operations during his years in the NWA. He also captured the Central States Heavyweight Championship on eight occasions and the Missouri Heavyweight Championship seven times.

So alongside the product coming out of St. Louis, Muchnick’s Wrestling Club, Missouri, was the place to be and be seen if you worked in the NWA.

In 2017, he fell in his home and broke both legs, one in multiple places. He continued to promote his WLW while he was on the mend.

Unfortunately, Race developed lung cancer, which proved to be the one battle he couldn’t win. Harley Race passed away in his home in Quitman on August 1, 2019. He was seventy-six years old.

While Central States Wrestling / Heart of America Sports Attractions may not have been the juggernauts of the territorial system that an AWA or WCCW may have been, it was the sister promotion to the St. Louis Wrestling Club.

Those two promotions together formed the spearhead of not only the formation of the NWA but its backbone in the country’s center as grand territories rose around it.

It was a conduit for many of the most outstanding workers in the history of the business to funnel through as they traveled the "NWA corridor" from St. Louis to Texas.

From “Big O” Bob Orton, “Nature Boy” Roger Kirby, Tarzan "Killer" Kowalski, and Sonny Myers in the early days to guys like The Stomper, Mike George, Black Angus Campbell, Wild Bill Longson, Danny Little Bear, and Bob Sweetan in its heyday, all the way to more familiar names like Bill Dundee and Tully Blanchard near its closing.

All the big names made Central States Wrestling a stop on their traveling calendar.

We hope that one result of our Wrestling Territories series is that you are building an appreciation for the legacy of this great business we all love and even learned a few things about this unsung territory.

Never forget: our wrestling history is gold!

Listen to Pro Wrestling Stories’ own Jim Phillips, Dan Sebastiano, and Benny Scala discuss the glory days of the Central States wrestling territory on Dan and Benny In The Ring:

These stories may also interest you:

- Verne Gagne and the Rise and Fall of the AWA

- A Ghost Story: How a Long-forgotten Territory Still Haunts WWE

- Ann Gunkel and the NWA’s Heated Battle for Atlanta

- The Rise and Fall of Mid-South Wrestling Association

Can’t get enough pro wrestling history in your life? Sign up to unlock ten pro wrestling stories curated uniquely for YOU, plus subscriber-exclusive content. A special gift from us awaits after signing up!

Want More? Choose another story!

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, and Flipboard!

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

"Evan Ginzburg’s stories are a love letter to wrestling, filled with heart, humor, and history. A must-read for any true fan." — Keith Elliot Greenberg

Wrestling Rings, Blackboards, and Movie Sets is the latest book from Pro Wrestling Stories Senior Editor Evan Ginzburg. 100 unforgettable stories—from sharing a flight on 9/11 with a WWE Hall of Famer to untold moments in wrestling history. A page-turner for fans of the ring and beyond. Grab your copy today! For signed editions, click here.

Pro Wrestling Stories is committed to accurate, unbiased wrestling content rigorously fact-checked and verified by our team of researchers and editors. Any inaccuracies are quickly corrected, with updates timestamped in the article's byline header.

Got a correction, tip, or story idea for Pro Wrestling Stories? Contact us! Learn about our editorial standards here. Ever wanted to learn more about the people behind Pro Wrestling Stories? Meet our team of authors!

ProWrestlingStories.com participates in affiliate marketing programs. This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we may earn commissions at no extra cost to our readers. This supports our mission to deliver free content for you to enjoy!