In an era where blood, gimmicks, and chaos sold tickets, St. Louis Wrestling Club dared to do things differently. Under the steady hand of legendary promoter Sam Muchnick, the Gateway City became the gold standard for professional wrestling. No chairs flying, no referees bumped, no circus acts. Just pure, believable wrestling that treated fans like sports fans. But when St. Louis strayed from its foundation, the fallout wasn’t just boos from the crowd. It was near riots, shattered glass, and a promoter’s reputation pushed to the brink. This is the story of how the St. Louis wrestling territory earned its unmatched respect, and three dark moments that almost tore it all down.

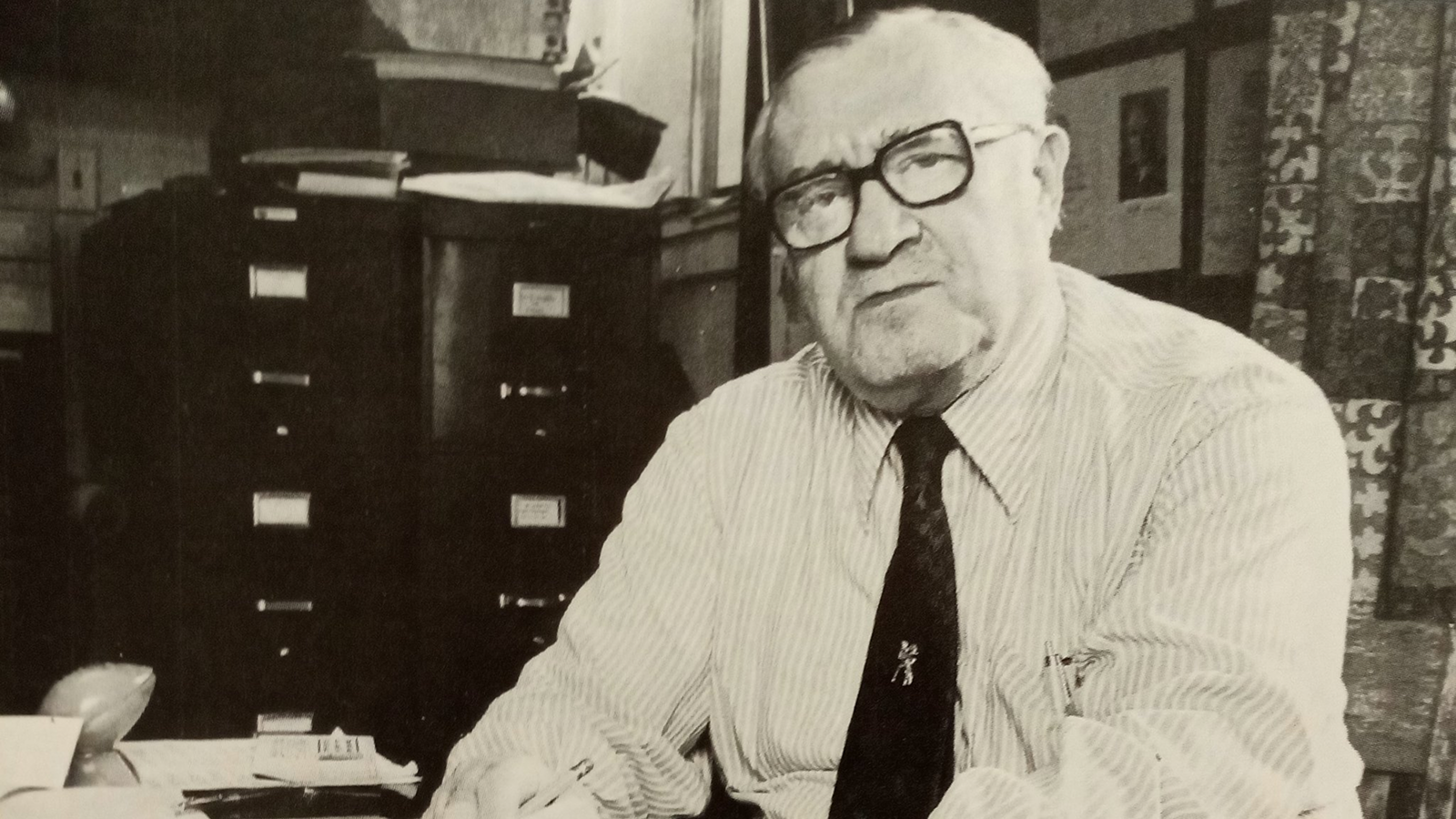

Sam Muchnick and the Blueprint of St. Louis Pro Wrestling

Throughout its history, St. Louis was considered one of the most conservative wrestling territories in the National Wrestling Alliance, perhaps the most conservative of all.

Its promoter, Sam Muchnick, served as a longtime NWA President and, for many years, also played a key role in booking the NWA World Champion.

Sam approached wrestling in St. Louis more like a baseball pennant race, focusing on steady competition and the pursuit of the title. In contrast, other promotions relied heavily on constant changes, wild gimmick matches, and heated personal feuds.

St. Louis was widely known as the best “payoff town” in the business. If Sam owed you exactly $250.37, you could count on receiving that amount down to the last cent.

Speaking to Slam Wrestling, Lou Thesz reinforced how much integrity he thought Sam Muchnick had.

"Sam was a very straightforward promoter. He paid you right on the barrel head, even if the house wasn’t that good that night. He was the most liked and loved promoter in the world."

When the territory was booming, main-event talent could earn $5,000 or more for a single show. These generous payouts typically came when Sam Muchnick promoted events at the St. Louis Arena, which seated up to 20,000 people, compared to the 12,000-capacity Kiel Auditorium. Sam adhered strictly to a set payout percentage, a consistency that earned him the respect of every wrestler who understood the business side of the sport.

To share a little bit more about Muchnick and how he operated, on one occasion, the matches had to be cancelled due to unforeseen issues. Sam offered to cover the wrestlers’ travel expenses so they could return to their home territories without them having to pay out of pocket.

In response to this offer, the talent, led by Johnny Valentine – a legitimate tough guy and one of the most respected voices in the locker room, as well as father of WWE Hall of Famer Greg "The Hammer" Valentine – refused to accept the money. Their respect for Sam ran deep. He had a rare quality among promoters: honesty and professionalism.

In Roger Deem’s The STRAP: A Complete History of Sam Muchnick’s Missouri State Championship, Sam Muchnick explained how fair, equitable treatment of his wrestlers was a priority.

"I always tried to be fair with everyone. That’s how I did business."

Only Houston promoter Paul Boesch came close to matching Muchnick’s sterling reputation.

Sam Muchnick’s booking formula was strict, and it was to keep the matches credible.

Jim Cornette spoke of his respect for the St. Louis pro wrestling product on an episode of the Jim Cornette Experience.

"St. Louis was the gold standard for wrestling television. Sam Muchnick ran a tight ship, and the presentation was top-notch. The fans were knowledgeable, and the talent was some of the best in the world. Wrestling at the Chase was a class act, and it set the bar for how wrestling should be presented on TV."

Ever since winning the promotional war for St. Louis in the 1940s against Tom Packs, Sam had been committed to presenting wrestling as a serious sport, even to the most casual fans.

His rules were clear: don’t touch the referee or put them in compromising positions, avoid silly gimmicks, and never use special stipulation matches unless they were fully justified.

For many years, Bobby Bruns served as Sam’s booker. When Bruns retired around 1968, Pat O’Connor took over. Pat generally followed the same philosophy, keeping the booking in line with Bruns’ style.

However, he was occasionally swayed by trends from the other territories, though those influences were usually stopped before they could take root. Muchnick wouldn’t allow current trends to dictate how he orchestrated his pro wrestling.

Then, on the morning of February 10th, 1973, during a taping of Wrestling at the Chase, something slipped through.

1. Terry Funk’s Chair Attack on Johnny Valentine – The Finish That Broke Every Rule (February 1973)

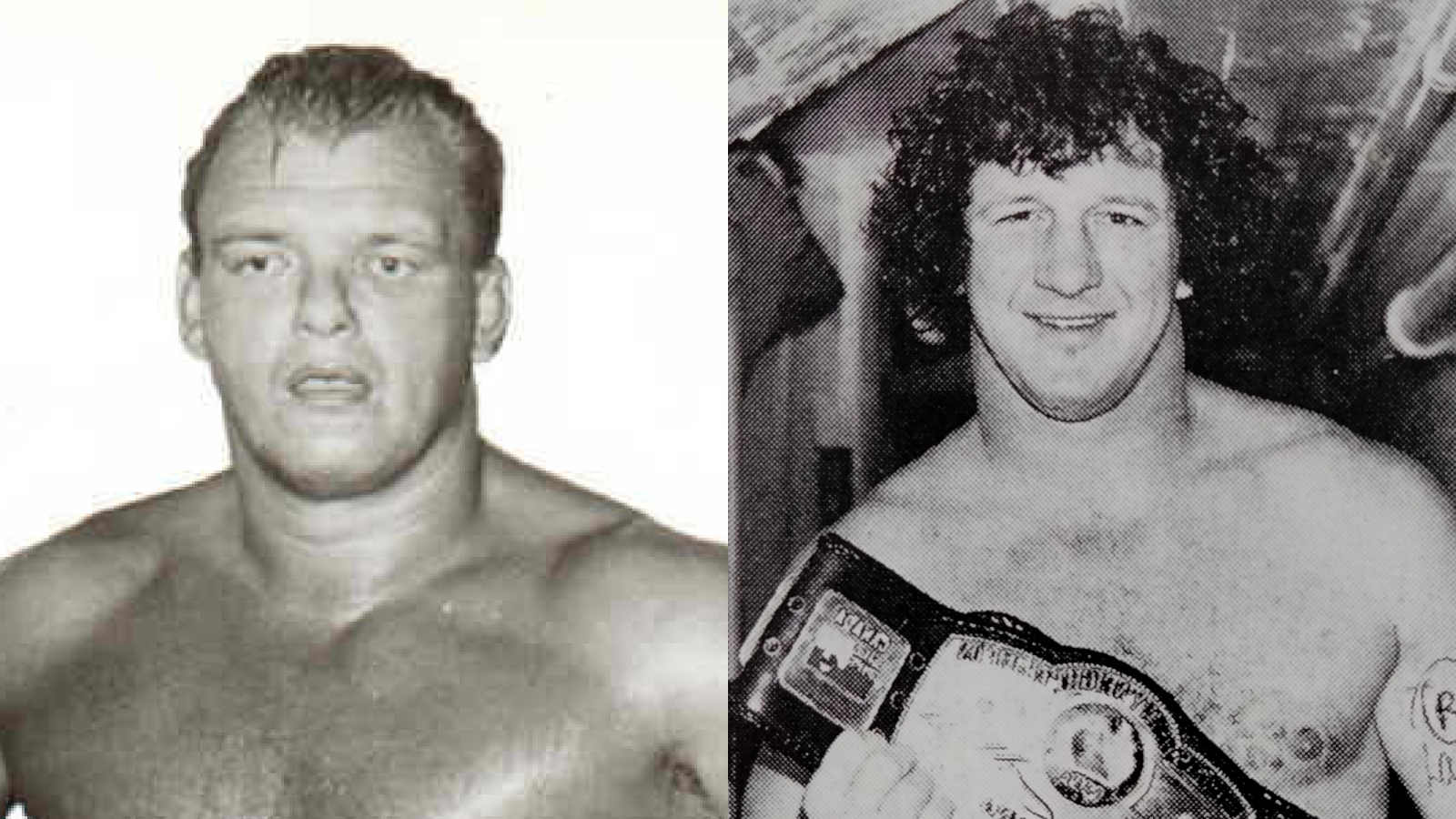

During a taping of Wrestling at the Chase on February 10th, 1973, Sam Muchnick had prior engagements and arrived late to the TV studio. In his absence, a match with a particularly poor finish aired, marking the first time the town saw such a low-quality ending broadcast on television. The match in question featured Missouri Champion Johnny Valentine defending his title against Terry Funk.

The plan was for Funk to win the championship, but the way it was done broke every rule of credibility Sam Muchnick had worked so hard to establish.

In front of referee Joe Schoenberger, Terry Funk blatantly used a steel chair to attack Valentine’s leg, then secured the victory via submission with his spinning toehold.

It was everything you didn’t do in St. Louis. It was an over-the-top finish that not only strained believability but, worse, shifted all the heat onto the referee. In Muchnick’s eyes, that was a cardinal sin of professional wrestling.

Sam Muchnick’s Response to the Terry Funk Title Win

When Sam Muchnick arrived at the studio between TV tapings – typically three episodes were filmed in a day – fans immediately swarmed the approachable promoter, voicing their outrage over what they had just seen.

Muchnick rushed to the control room to review the match. Upon watching the finish, he was livid. Turning to Pat O’Connor, he snapped, "In St. Louis you put a finish out there like that? My God…"

It was nothing short of a miracle that O’Connor kept his job after that.

Muchnick quickly decided that Funk would drop the title back to Valentine in a rematch scheduled for March 16th, 1973, at the Kiel Auditorium. However, plans changed when Valentine was hospitalized in Houston due to a heart condition. As a last-minute replacement, former NWA World Champion Gene Kiniski was brought in and crowned the new Missouri Champion.

Despite the original plan, Terry Funk would not hold the Missouri title following the controversial TV taping.

2. The Sheik vs Pat O’Connor: The Match That Never Made the Ring (August 1974)

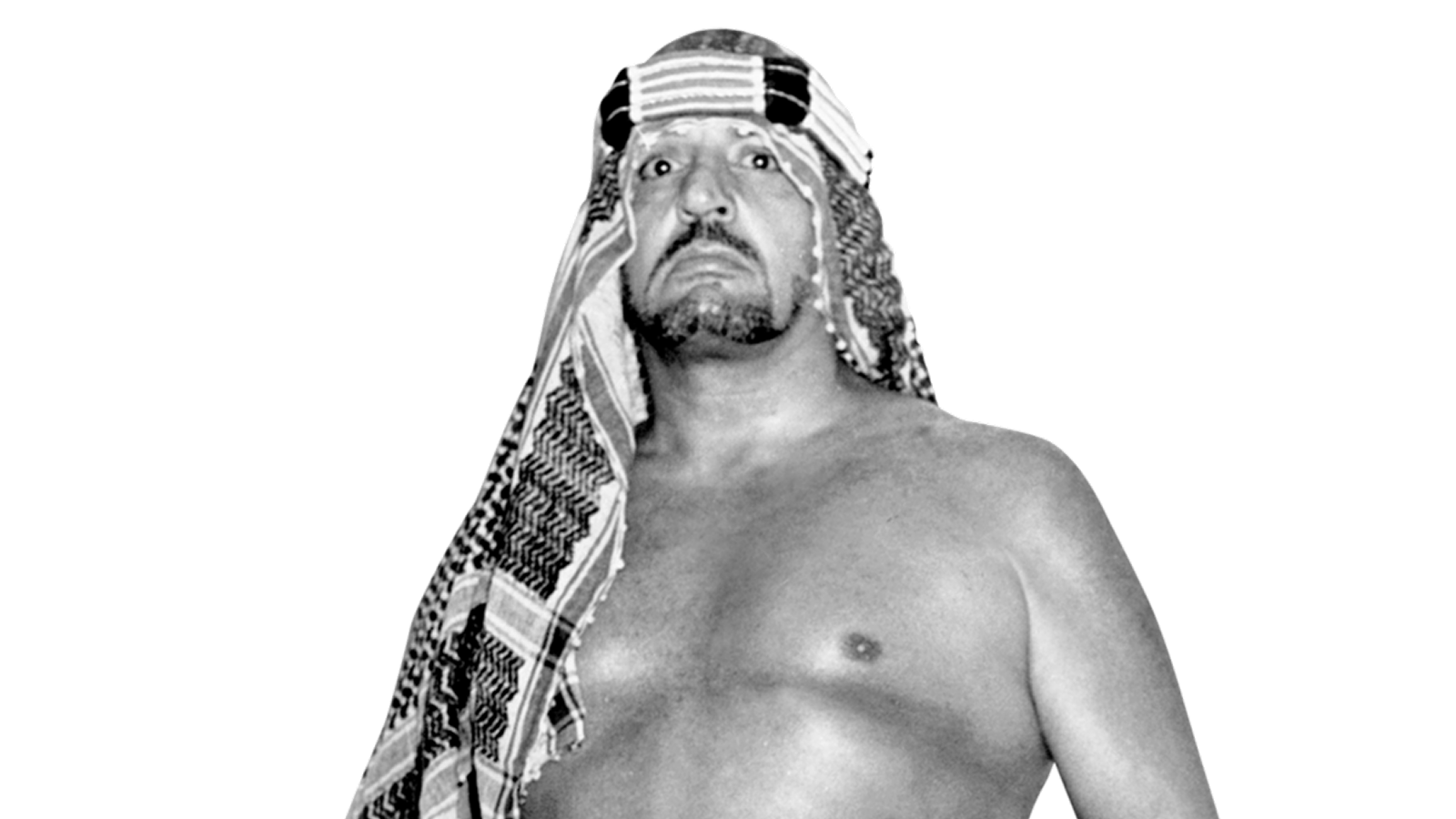

On August 9th, 1974, The Sheik was scheduled to face Pat O’Connor in St. Louis. Given the city’s reputation for presenting hard-hitting, competitive, and credible wrestling, this booking came with some obvious concerns.

Sam Muchnick likely had reservations, knowing The Sheik’s reputation in Detroit – his home territory – for wild brawls, disqualification finishes, and bloody spectacles.

What unfolded that night was exactly what not to do in a town built on the art of in-ring storytelling and athletic credibility.

The match between The Sheik and Pat O’Connor never officially began. Before announcer Larry Matysik could even introduce the participants, The Sheik ambushed O’Connor on his way to the ring. Armed, as always, with an assortment of foreign objects, including his trademark pencil, The Sheik delivered a brutal beatdown.

This kind of chaos simply didn’t happen within the walls of the Kiel Auditorium.

To make matters worse, The Sheik had brought along his manager, Eddie Creachman, despite Sam’s clear stance against managers in St. Louis, with Bobby Heenan being the lone exception.

Creachman stood on the ring apron, stirring up the crowd and adding fuel to an already volatile situation. The sheer unpredictability and violence of the attack pushed fans to the edge. And then came the final straw. The match was declared a disqualification win for O’Connor before it had even officially started.

The crowd erupted in fury. A riot felt imminent.

In a city that prided itself on classy, sportsmanlike wrestling, this kind of chaos threatened everything Muchnick had spent decades building. What if a child got hurt? What if longtime fans swore off wrestling for good after such a spectacle?

Thankfully, police on-site were able to restore order before the situation escalated further. But it was a close call and a vivid reminder of what could go wrong when the established standards of St. Louis wrestling were ignored.

To say Sam Muchnick was livid would be an understatement. Furious over the chaos and damage done to the city’s carefully protected reputation, he turned to Pat O’Connor and said, "This is how you kill a great town."

The following Monday, Ed Farhat (The Sheik) called the St. Louis office in an attempt to smooth things over. He was booked for one more appearance at the next Kiel Auditorium show, where he quickly defeated Devoy Brunson in a two-minute squash match.

That would mark the end of The Sheik’s run in St. Louis, and the end of that kind of wild, out-of-control presentation in a territory that prided itself on credibility, professionalism, and restraint.

3. Harley Race vs Johnny Valentine: Wrong Town for a Bad Finish (April 1975)

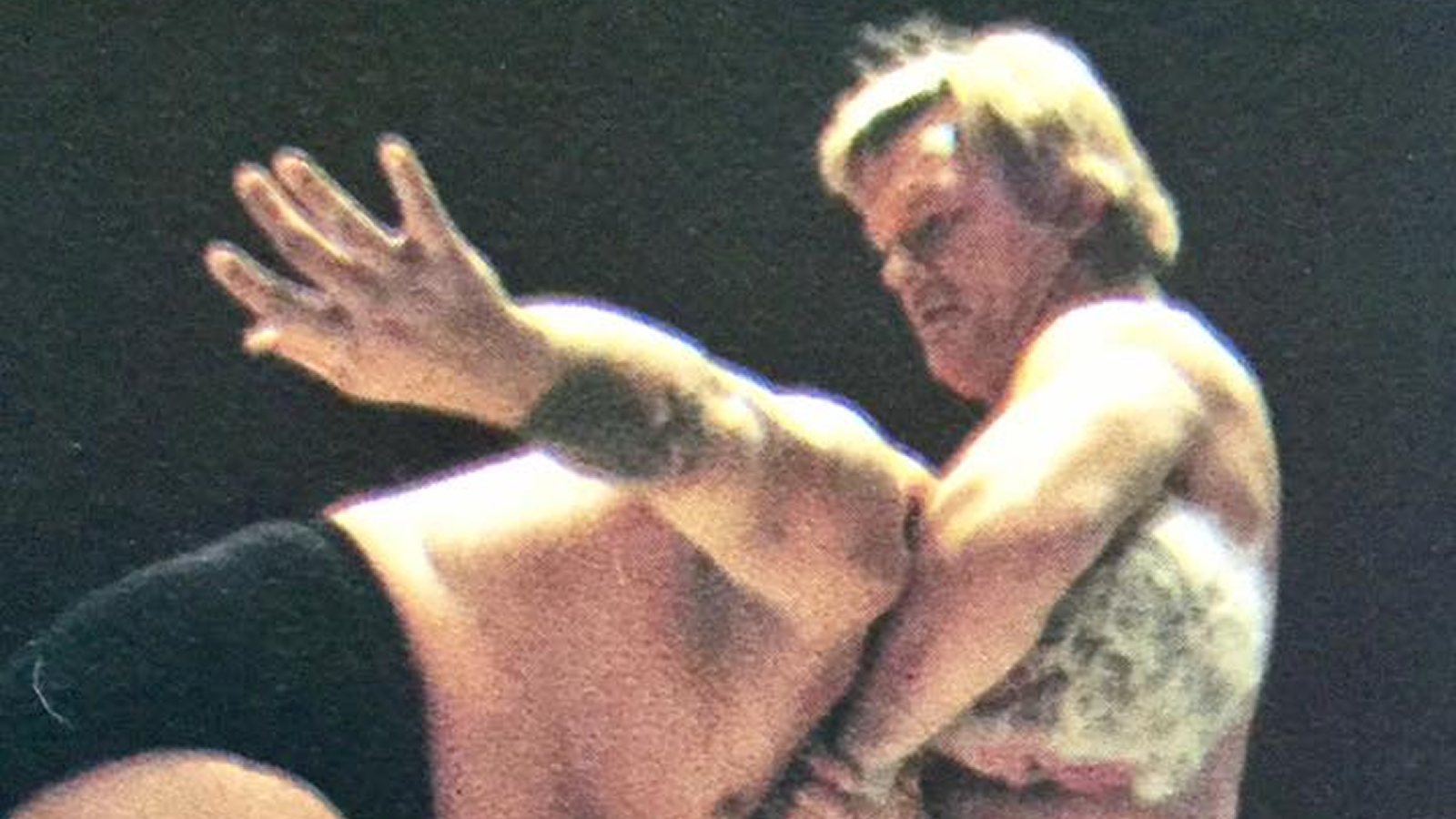

Perhaps the worst fan reaction in St. Louis wrestling history occurred on April 18th, 1975, at the Kiel Auditorium.

Harley Race was defending the Missouri State title against local favorite Johnny Valentine in a two-out-of-three falls match. The finish, clearly designed to avoid a clean loss, saw Race win the deciding fall while Valentine’s leg was visibly draped over the bottom rope. Referee Frank Diamond, brought in from the Kansas City territory, either missed it or ignored it. He quickly exited with Race, sensing the crowd’s growing hostility.

As announcer Larry Matysik began to call the outcome, he noticed something flying toward the ring. He instinctively ducked just in time, and a beer bottle smashed into the ring light above, shattering on impact. Glass rained down, and Matysik was cut in the head by the debris. He and Valentine quickly made their way out of the arena.

Moments later, another bottle was hurled, skidding across the mat and striking Ray Gillespie at the press table.

Enraged fans began to swarm the ringside, looking for the referee. He was long gone.

Police assigned to the auditorium managed to get the situation under control, preventing what could have been a full-blown riot.

In the days that followed, Sam Muchnick didn’t hold back. He was overheard warning anyone who would listen: "A family could have been there for the first time. What if their kid was hurt? What kind of impression would that leave? Those families won’t come back!"

The Lasting Impact of Bad Finishes in St. Louis

In many wrestling territories across North America, promoters and wrestlers often wore riots like a badge of honor. It was a signal that they had provoked strong reactions and drawn intense heat. These chaotic moments were sometimes even seen as a sign of success.

But St. Louis was a different kind of wrestling town. Sam Muchnick built the territory on trust, realism, and professional integrity. For him, and for the fans who filled venues like the Kiel Auditorium, "bad heat" wasn’t worth the price. A riot didn’t signal excitement. It signaled a serious problem. It meant the fans felt cheated, and that kind of betrayal cut deep in a market that prided itself on legitimacy.

When a questionable finish occurred, especially one that made the referee look incompetent or dishonest, it wasn’t just a one-night issue. In St. Louis, a finish that broke the unspoken contract with the audience could lead to long-term consequences.

As Muchnick had worried, families might decide not to come back. Loyal fans could sour. The reputation of the promotion took a hit that couldn’t be fixed overnight. Sam understood this better than most. He recognized that credibility took years to build and only seconds to lose. His frustration over bad finishes wasn’t just about maintaining order. It was about protecting everything he had spent decades cultivating.

Even for a territory with as much prestige and goodwill as St. Louis, no place was immune to the consequences of a poorly executed or out-of-place ending. A single night of chaos could undermine months of careful planning and erode the unique relationship between the promotion and its fans.

While other promoters chased cheap heat and shocking moments, Muchnick fought to preserve wrestling as a respected sport.

On an episode of Something to Wrestle With, Bruce Prichard shared his experience working with Sam Muchnick.

"He had a way of making you understand the business without saying much. He respected the tradition and taught us to do the same. His influence was felt throughout the industry, and his legacy is undeniable."

In the end, the legacy of St. Louis professional wrestling wasn’t defined by riots or gimmicks. It was defined by its unwavering commitment to doing things the right way, even when others didn’t.

These stories may also interest you:

- When Wrestling Goes Bad: The 1957 MSG Riot

- Big Van Vader and Antonio Inoki Incite a Riot in Sumo Hall

- 1997 WWE Riot: Fans Rage Out of Control at House Show

Can’t get enough pro wrestling history in your life? Sign up to unlock ten pro wrestling stories curated uniquely for YOU, plus subscriber-exclusive content. A special gift from us awaits after signing up!

Want More? Choose another story!

Be sure to follow us on Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, and Flipboard!

Our wrestling history is gold, and so are readers like you!

If this story added to your collection of wrestling knowledge, you can say thanks:

Tip jar (PayPal)

Browse our merch at our brand-new shop (launched February 2026)!

Pro Wrestling Stories is committed to accurate, unbiased wrestling content rigorously fact-checked and verified by our team of researchers and editors. Any inaccuracies are quickly corrected, with updates timestamped in the article's byline header.

Got a correction, tip, or story idea for Pro Wrestling Stories? Contact us! Learn about our editorial standards here. Ever wanted to learn more about the people behind Pro Wrestling Stories? Meet our authors! Want to write for us? Learn how to join the team.

ProWrestlingStories.com participates in affiliate marketing programs. This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we may earn commissions at no extra cost to our readers. This supports our mission to deliver free content for you to enjoy!